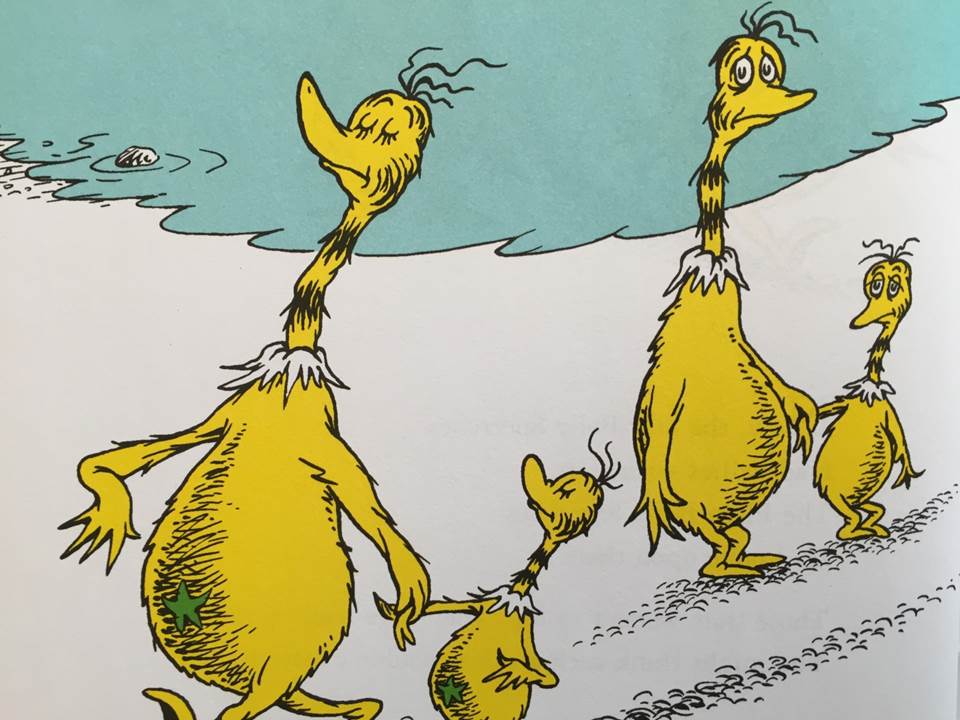

One of my favorite Dr. Seuss books of all time is the lesser-known tale of the Sneetches. A race of odd-looking, Seussical animals known as “sneetches” lived on beaches, but the species was divided into two groups: those with stars on their bellies and those with no stars. As it happened, the ones with stars looked down on the ones without, refusing to speak to them or socialize. “We’ll have nothing to do with the ‘Plain-Belly’ sort!” It seems such a small thing—a star—and Geisel adds knowingly that you wouldn’t think it something that mattered at all. A salesman arrives and invents a machine that can place stars on their bellies, and later, another that can remove them—for a price. Chaos ensues. Stars are coming and going as fast as can be. The point is clearly made: there will always be superficial things that divide us, but the trick is finding the core things we have in common.

I have often felt a little this way about Christianity. Growing up, it felt like there were concentric circles of orthodoxy around my life and my community, divisions that separated us from one another in some meaningful way. We would drive past these other churches with weird names like Episcopal or Methodist and I’d wonder silently to myself if they were one of “us” or one of “them.” We gravitate towards tribes, but this isn’t just a religious thing—it is a human thing. As humans, we’ve always had an easier time celebrating the things that divide than standing on what we have in common. To be tribal is to be human; unity demands the divine.

As a devout Christian, I would like to believe that the gospel is something that should unite us, but our track record is not so good. As it turns out, tribalism has been dividing Christianity from the very inception, even though it shouldn’t have. What we have in common is so much greater than our differences! The problem is not that we don’t want unity enough, but that we are blind to tribalism in ourselves, as well as the way that it corrodes community and undermines the gospel. This is played out in the first real conflict of the early church in the book of Acts.

1) The People

The book of Acts opens with a small group of Christians gathered for prayer, and meeting with a not-yet-ascended Jesus. This is quite an homogenous group. They are all Jewish. They are probably all locals. Some are related. Many have known one another forever. But something is about to happen that will blow that away. On the Day of Pentecost, thousands of people from other cultures—many Jewish—are gathered in Jerusalem. The Spirit falls in power and the disciples begin speaking and preaching in many languages. Thousands are added to the church. They go from being incredibly homogeneous to incredibly diverse…in just one day.

At the end of the chapter, however, we are shown a picture of a surprisingly unified community. It is such an astonishing picture of what church ought to be that the passage has become standard fare in our pulpits. It concludes in a striking way: “All who believed were in one place, and had all things in common, and sold their possessions and goods, and divided them among all, as anyone had need.”

The key word here is “in common,” which is the Greek word “koinonia.” Now, whenever I have taught this passage, people get a little uncomfortable at this last part. For Americans, the specter of communism hangs over those words, and that scares them. But “in common” goes even deeper, and perhaps that scares us even more. What it signifies is the radical elimination of divisions between us, not just the obvious one of property, but the more subtle one of identity. We now identify with Christ and His body before any other tribe. The gospel is meant to collapse tribalism by creating a new allegiance. That will be tested a few chapters later.

2) The Problem

“Now in those days, when the disciples were multiplying, there arose a complaint against the Hebrews by the Hellenists, because their widows were neglected in the daily distribution.” People were selling their possessions and bringing the money to the disciples for distribution to the needy, but apparently the proceeds were not being distributed fairly. Instead, it was happening along tribal lines. This is truly the definition of tribalism. When tribal loyalties cause us to exclude others and discriminate—not necessarily against outsiders, but in favor of our own—it is called tribalism. As a result, tribalism dissolves broader unity.

The solution was fairly simple and it is played out in what follows. The most obvious problem was that the leadership needed to be diversified. As the church had grown beyond that initial homogenous group, leadership needed to change and become multi-cultural. That is really a good lesson for us today, and it is just what they did. They chose seven people to handle the daily distribution, and if you look closely at their names, you will see that they are all Greek. Unfortunately, that addressed only half the problem—the structural one. A deeper one existed.

Let me ask you a question. Do you think that the Jewish people handling the distribution of bread intended to discriminate against the Greek widows? We’ve just seen two descriptions of this incredibly loving and generous community. They saw themselves as completely unified by the gospel, so bereft of any divisions that they liquidated their own property to help one another. Widows would have been the most vulnerable people in their culture. Was it on purpose? Of course not.

Tribes lock down the deepest allegiances in our lives, but unfortunately, they are very often invisible to us. You only recognize those divisions when you are on the outside of the tribe looking in, like the Greek widows were. The only way that you can possibly see the exclusion they cause is to step outside of yourself and see your tribe as others can. It requires asking self-aware, other-centered questions of your choices, like “Does this include or exclude others in the community?” No matter how compelling the message of the gospel is, it won’t change anyone unless we first welcome it to rearrange our own tribal prejudices on the deepest level.

3) The Challenge

Over the last two centuries, Christians have become experts at locating their superficial differences and allowing them to divide—not because we are religious, but because we are human. I could reach back into church history for a myriad of examples, but I have only to look at my Facebook newsfeed to see it happening in real-time. One person doesn’t believe in the sign gifts, and believes that those who do must be charlatans or deluded. Another champions Calvinism, and speaks as if those who don’t are nominally Christian. Another is politically progressive; how could he possibly be a Christian? (wink) The list goes on and on. We create little tribes around each of these issues and divide from one another over and over until Christianity is little more than a patchwork quilt of tribal preferences.

The problem is that with the worldwide situation today, nobody really needs to find yet another entity to divide us. Division is tearing our world apart, whether religious or political extremism, on the right or on the left. Post-Christian people look at religion and say, “Why would I ever want to get involved with that?” No one needs another tribe to claim their loyalty and spur dissension. Instead, what they really need deep down is something to give their lives meaning, to connect them with one another in deep community, to give them value and the power to live life in a way that is redemptive and restorative. The gospel can do that; however, it requires that we learn to live out of what we have in common.

Interestingly, the Apostle Paul dealt with tribalism over and over. He writes in Galatians 2 that when he returned to Antioch, he rebuked the Apostle Peter to his face for tribalism in the way that he behaved around Gentiles. Paul then takes the opportunity to clarify what the gospel means. I won’t attempt to summarize that amazing chapter, but at the end he writes the following: “For you are all sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus…There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” It is about unity, and that is something that requires the divine. They have a new family because they have a new father; they need to see themselves and one another differently, and it needs to start right away.

How did the Sneetches get over their issues? The story doesn’t really say. Maybe after so many trips through the machines, they just got tired of the whole thing. In the book, Geisel says that with stars coming and going so quickly, they got a little confused about who was who. I doubt that it happens that way in real life. But I do wonder something: maybe they began to see life from another perspective.

I challenge you today to step outside of your tribe. Have a real conversation with someone who sees things differently from you. Begin a friendship with someone with a different background than you. Create a new network that is OUTSIDE of your normal routine so that you start to meet people who are unlike you. Step out of your comfort zone and get a little curious about people in general. Start to ask questions about how they came to see things the way they do. Perhaps you will find, along with the Sneetches that it begins to be hard to see who is who.

Daniel Radmacher © 2017

Good word brother. I appreciate the language of “tribalism.” It’s a good descriptor of the many areas (race, theological particulars, political preference, geography) where we like to find and take comfort in “our people,” whatever that means . . . Gal 3:28 and its parallels cuts through all those lines: “Christ is all, and is in all.”

Strong writing here, Dan. You have helpfully articulated the concern. It is interesting how the New Testament passages you’ve aptly highlighted reveal the human nature tendency among the early believers — showing that we are not so unlike them — as a reality that must be challenged. There is a higher calling: to view one another thru a lens of being unified in Christ. If in Christ, we are on the same team, in the same family.

Surely for believers there is a way forward. Thanks for the practical tips as well. I think for many of us (who were raised in “Fighting Fundy” circles among fairly new denominations or associations whose reason for existing was to establish or deny particular doctrinal distinctives) this is a necessary pursuit to overcome our subcultural baggage.